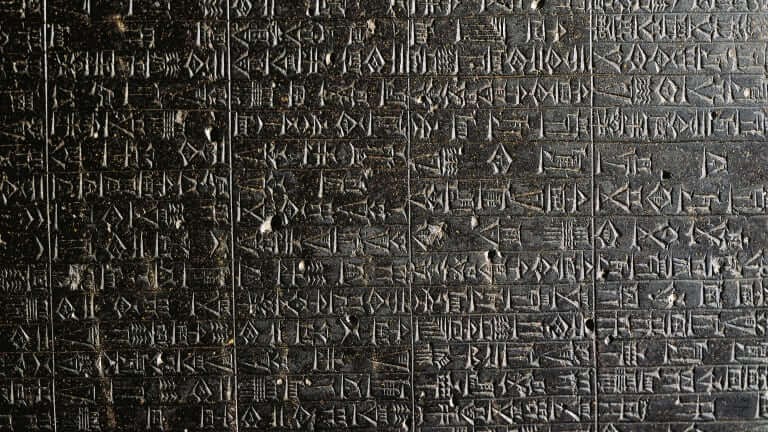

For thousands and thousands of years, human beings have tried to measure time. Scientists did their math by inventing sundials, calendars, hourglasses and clocks of any kind only to satisfy the tracking of our perception that time does pass by, even when we’re working. The first worksheet noting tasks, work hours and pay dates back to 1772 b.C with the Hammurabi Code and since then, similar attempts have been made by the ancient Egyptians, the greeks, the Chinese and the Romans.

It is no surprise that during the 13th century, medieval artisans began to make mechanical clocks commissioned by the Church so that the monastic community would know when it was time to gather together for prayer. That way, by ringing the bells of the local church, the whole community in the nearby village would participate in the religious activity at the same time. It’s incredible how such an old practice is still part of our everyday life: we can rest assured that every church bell will ring at noon and at vespers’ time.

Although this method was quite alright for rural villages during the middle ages, unfortunately, it wasn’t enough for scientific experiments, sea sailing or contexts where high precision was needed. And yet, all around the globe, most people lived without clocks until the first half of the 1900s. For hundreds of years, farmers, fishermen, merchants and artisans woke up at the crack of dawn to go about their daily tasks and came home when the sun went down without caring about what time it was. People’s schedules were driven by nature only: sunlight, seasons and weather, so even their daily activities would change much from one season to another.

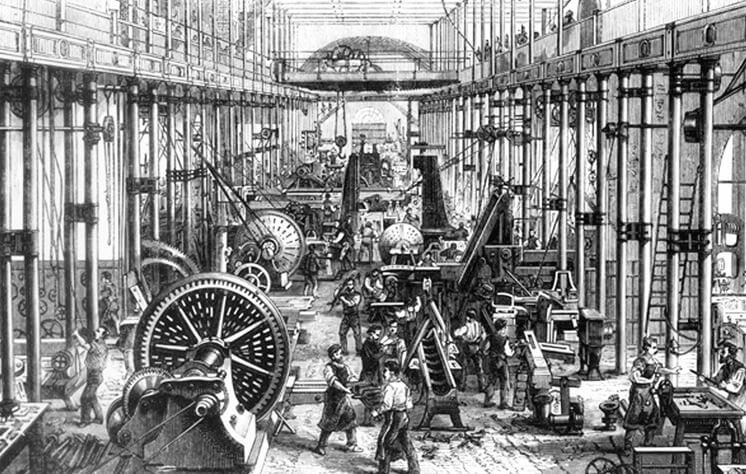

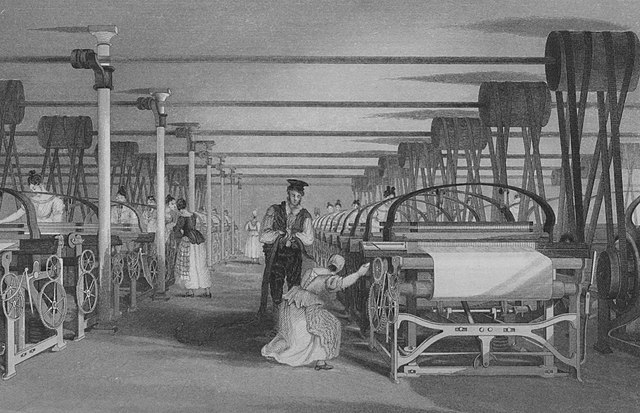

Around 1750 technology in the manufacturing industry introduced new machines powered by steam engines which modified the history of humankind forever. Work pace became frenetic and in order to sustain such a higher production volume, factories needed constantly-performing workers who would keep fires always going or change thread spools at the speed of light.

The arrival of the industrialisation (1750 – 1870)

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, all those workers recruited in the countryside who hadn’t been worrying about time until that moment, suddenly found themselves lining up to clock in, at the same hour, every single morning. Entrepreneurs spent an incredible amount of time managing the people working for them so they hired clerks whose job was to take note of the time workers arrived at work and they did so by using spreadsheets, direct ancestors of modern Excel spreadsheets.

Basically, in each factory, workers were expected to be punctual if they didn’t want their pay to be deducted (or any other punishment the rulebook stated). In the state of New York, Mr Benjamin Hacks installed a giant clock in his factory so he could track production times. In Massachusetts, textile industries adopted a system of bells ringing when the gates would open, when breakfast and lunch were served and when the shift started. Often bells were replaced with the steam engine’s whistle which could be heard from the houses where workers lived so they could get off the bed and go to work.

A new century

The turning point towards automatic time-tracking clocks was at the end of the 19th century with the first experiment made by Williard Bundy who, by associating the typewriter mechanics to a clocking system, managed to obtain a report of the hours worked by each worker. A second attempt was made by Alexander Dey in 1893 with a mechanical gripper on a wheel which the worker could action by using his employee number. But it was Daniel Cooper who in 1894 built a clock in which you could insert a card and get a stamp on it with the time of the entrance of every single worker in the factory.

Cooper’s invention was a real success and quickly spread across the Country. In the same year the Bundy Manufacturing Company was founded, the first real producer of time-tracking clocks, which, after a few acquisitions, became the International Business Machines in 1911, better known as IBM. The company worked on clocks for many years before focusing exclusively on computers.

In 1915 at Ford Motor Company you could find as many as 129 time-tracking clocks in synch with a master clock set on Detroit time. The “clock manager” was in charge of checking each clock every single day to make sure everything was up and running, and if that wasn’t the case he could use one of the six spares in the warehouse.

A new millennium

At the end of the 70s, the way is paved for clocks able to communicate with payroll software. In Italy, innovation comes from Zucchetti, who already presented the first time and attendance software in 1986.

And it is at the beginning of the new millennium that technology strikes again with digitalisation: the old card becomes a “badge” and after a few years this is made completely virtual thanks to applications and software which we can now use from the comfort of our smartphones, anywhere and anytime, even with biometric technology.

It’s safe to say all the actions one must once do to say they clocked in and out don’t reflect our society anymore. The same tasks today are brought to the minimum effort making HR processes extremely easier and efficient.

We cannot know what technology will bring us in the future and as we leave that job to innovation, we can only be grateful for the amazing perks our ancestors could only dream of.